How Jihadi John was tracked down in Syria

- 13 November 2015

- US & Canada

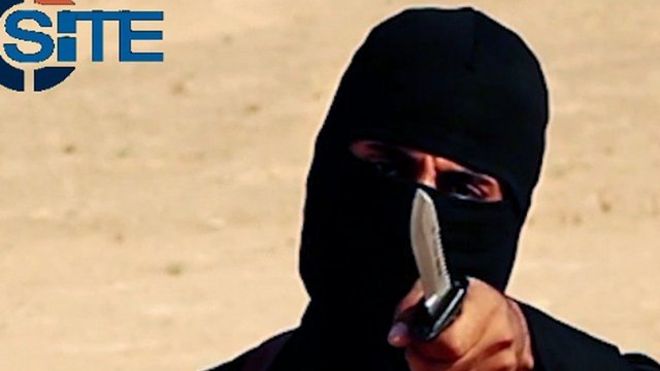

SITE Intel Group via AP

SITE Intel Group via AP

Mohammed Emwazi - or Jihadi John, as he was known - was apparently killed in darkness.

Officials on both sides of the Atlantic had been tracking him for some time, trying to sort out where he was - and how to "put him out of business", as one former US official said.

People around the world knew about him - and his chilling videos of the beheadings of Western hostages.

A naturalized British citizen, Emwazi, 27, grew up in West London. He studied computer programming at the University of Westminster and went to Syria to join Islamic State militants several years ago.

His victims in Syria reportedly included Japanese citizen Haruna Yukawa and journalist Kenji Goto; US journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff; Abdul-Rahman Kassig, who was also known as Peter, a British citizen; and British aid workers David Haines and Alan Henning.

Americans and Brits wanted him dead. "When people harm Americans anywhere," US President Barack Obama said, "we do what's necessary to see that justice is done."

Daniel Benjamin, who served as the US state department's top counterterrorism adviser under the Obama administration, said intelligence agencies in both countries would have been "working all of their sources to locate him and put him out of business".

A senior US administration official confirmed that officials from both countries worked closely together, explaining: "The United States and UK have consulted with each other regarding the targeting of Mohamed Emwazi."

Joshua Landis, a Syria expert at the University of Oklahoma in Norman, said intelligence officials were most likely were listening to "cell-phone activity". In addition, as Brett Bruen, a former National Security Council official, pointed out, Emwazi gave away "important details" about his whereabouts through his own, slickly-produced videos.

He stands, holding a knife, in a desert. His face is hidden, but you can hear his voice - and see his hands.

Intelligence and defence officials rely on a variety of sources while trying to figure out where someone is located. Brookings Institution's William McCants, author of The ISIS Apocalypse, said that they likely used "a mix of human intelligence and watching from the air".

On the human side, he said, Raqqa activists, "people who are disgusted with the Islamic State," tell him and others outside the country about the group - such as where militants spend time and where they've carried out some of their murders.

Evan Barrett, an adviser to an organisation that opposes the Syrian regime, the Coalition for a Democratic Syria, says he talks regularly with the activists from Raqqa. "They pass along information to us," Barrett says, "and we give it to the intelligence agencies".

As McCants explains: "They want the world to know what's going on." But it's a perilous undertaking.

Last month two Raqqa activists, Ibrahim Abdel Qader and Fares Hammadi, were killed in Turkey, and the Islamic State (IS) group claimed responsibility. The two men moved there because they'd received death threats and thought they'd be safe across the border.

Dominic Lipinski

Dominic Lipinski

Using different sources, intelligence and defence officials were able to sort out the location. For some time he was monitored from the air - "tracked carefully", said a senior US defence official.

He was killed by a drone. The strike, said University of Maryland's Gary LaFree, showed IS "is not invincible."

Defence officials sounded pleased - but also warned people not to exaggerate his importance.

Jihadi John was an IS "celebrity of sorts," Col Steve Warren, a Pentagon spokesman, told reporters. But, he explained, Emwazi "wasn't a major tactical figure."

Still Col Warren sounded pleased. "This guy was a human animal," he said, "Killing him is probably making the world a better place."

No comments:

Post a Comment